The Psychoacoustics of the Two-Tone Horn

- Jonathan Lansey

- July 15, 2025

- 7 mins

- Research

- bike safety cycling sound science technology

TL;DR;

- The Two Toned Horn: The typical car horn includes two speakers each physically able to play a single musical note continuously. Pressing the button triggers both of the speakers to play their individual notes in unison.

- The “Roughness” Sweet Spot: Horns are typically tuned to a major or minor third (ratios of 5:4 or 6:5). This interval sits in a specific region of the critical band that creates urgency through “roughness” without becoming unrecognizable noise.

- Cortical Preference: The brain’s pitch-processing circuits prefer “harmonic complexes.” A dual-tone horn presents a rich spectral structure that cortex neurons identify as a coherent “object” rather than random environmental noise.

- Neural Recruitment: Two tones separated by a sufficient frequency interval recruit more total auditory nerve fibers than a single tone of the same energy, creating a higher perceived loudness due to “spectral loudness summation”.

“The ear is the only sense that cannot be closed… the ear is always open.”

— Attributed to R. Murray Schafer (1977)

1. The Engineering Constraint: Loudness vs. Law

Before understanding the choice of notes, we must understand the limit of volume. Vehicle horns are governed by strict regulations (such as UN/ECE Regulation No. 28) which cap the maximum sound pressure level (SPL), typically around 105–118 dB at 2 meters.123

Given that a designer cannot simply increase the decibels indefinitely to get attention, they must increase the perceived loudness and urgency through spectral manipulation. This is where the single-tone horn fails and the dual-tone horn succeeds.

2. Physiology: Spectral Loudness Summation

The primary advantage of a dual-tone horn is a phenomenon called spectral loudness summation.4

2.1 The Basilar Membrane as a Fourier Analyzer

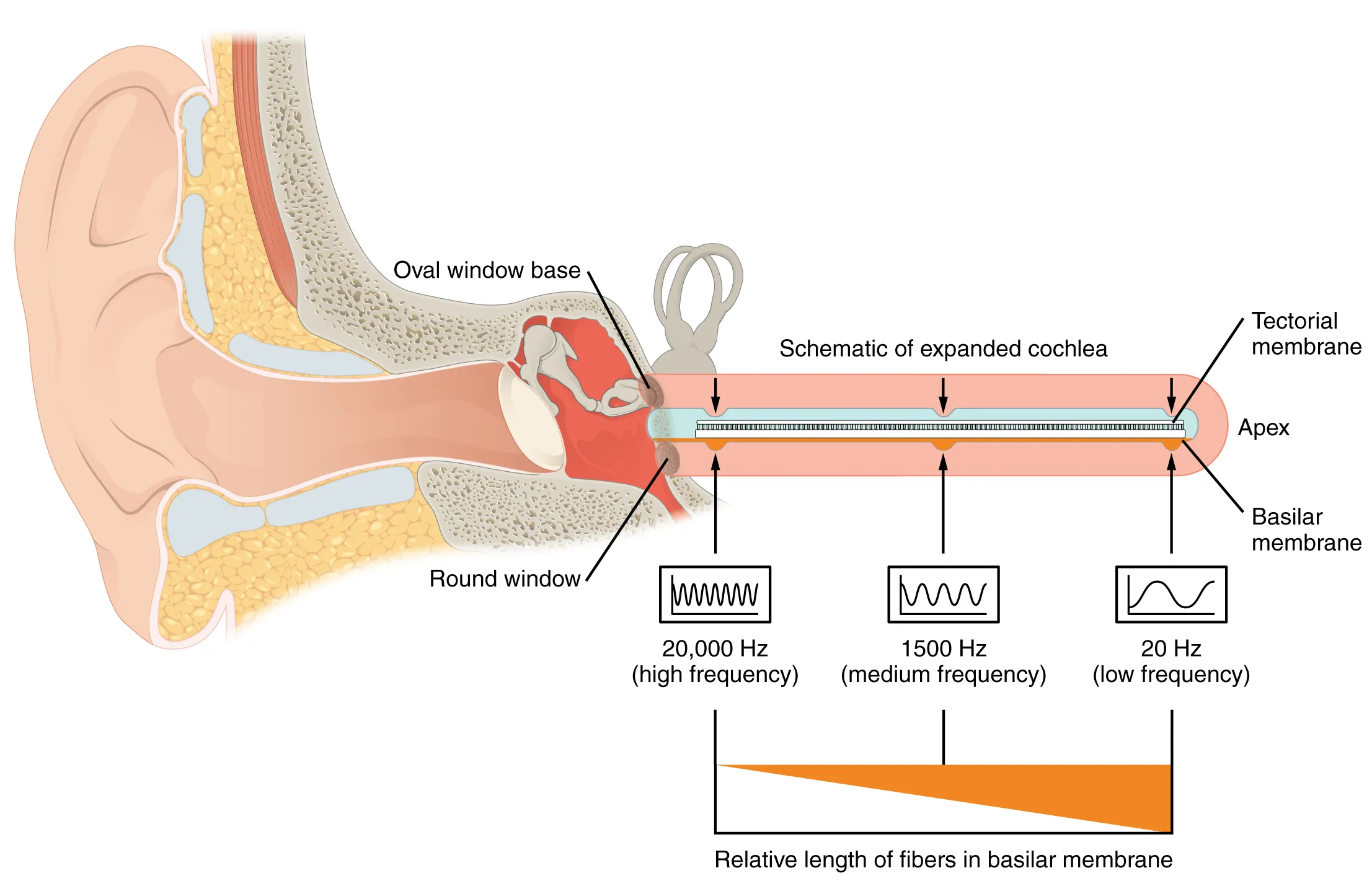

The inner ear (cochlea) organizes sound tonotopically. High frequencies vibrate the base of the basilar membrane; low frequencies vibrate the apex. A single tone activates a specific, localized population of hair cells and auditory nerve fibers.

Auditory nerve fibers have a limited dynamic range. As the intensity of a single tone increases, the firing rate of the stimulated fibers eventually plateaus—a phenomenon known as saturation. Pushing more energy into that single frequency yields diminishing returns in neural output.

2.2 Escaping Saturation

By splitting the acoustic energy into two distinct frequencies (e.g., 400 Hz and 500 Hz), the horn activates two separate populations of neurons along the basilar membrane.

Because these two populations are spatially separated, they do not compete for the same neural bandwidth. The brain sums the inputs from these separate channels. Consequently, two tones of 70 dB each will sound significantly louder than a single tone of 73 dB (the physical energy sum), because the neural recruitment is broader and less saturated.56

3. The Psychoacoustics of Intervals: Why a “Third”?

If two notes are better than one, why not any two notes? The answer lies in the Critical Band.7

3.1 The Critical Bandwidth

The ear analyzes sound in discrete frequency bands. In the range of car horns (300–600 Hz), the critical bandwidth is roughly 100 Hz.

- If tones are too close (< 50 Hz apart): They fall within the same critical band. They interfere with each other, causing slow “beating” or masking. The loudness advantage is lost because they are competing for the same neural patch.

- If tones are widely separated (> 200 Hz apart): They sound like two unrelated events, potentially confusing the listener.

3.2 The Plomp-Levelt Consonance Curve

In 1965, Plomp and Levelt mapped how humans perceive “roughness” (dissonance) based on frequency separation.78

They found that maximum roughness occurs when two tones are separated by about 25% of the critical bandwidth. As the separation approaches the critical bandwidth boundary, the sensation shifts from “rough” to “consonant.”

Car horns, typically tuned to a Minor Third (6:5) or Major Third (5:4), sit in a transition zone.9101112 They are:

- Distinct enough to be outside the masking threshold (maximizing loudness).

- Rough enough to trigger “sensory dissonance,” which commands attention and creates urgency.

- Harmonic enough to be perceived as a single mechanical device rather than a screeching anomaly.

4. Neuroscience: Cortical “Object” Detection

Beyond the ear, the brain has specific circuits for identifying “objects” in sound.

Research in auditory neuroscience has identified harmonic template neurons in the auditory cortex. These neurons are tuned to respond specifically to sounds that feature a fundamental frequency stacked with integer harmonics—the exact structure of a horn.131415

A dual-tone horn presents a “chord” of two harmonic stacks. This complex structure is more robust against environmental noise (like wind or tire roar) because even if one frequency component is masked by the environment, the brain can reconstruct the “object” from the remaining visible harmonics. A single pure tone offers no such redundancy; if its specific frequency is masked, the warning signal vanishes entirely.

5. Summary Table: Single vs. Dual Tone

| Feature | Single-Tone Horn | Dual-Tone Horn (Major/Minor 3rd) |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Recruitment | Localized; subject to saturation | Distributed; recruits wider population |

| Loudness Perception | Linear w.r.t physical intensity | Super-linear due to summation |

| Urgency | Dependent on pure volume | Enhanced by “roughness” (beating) |

| Noise Resistance | Low; easily masked by specific noise | High; redundant harmonic templates |

6. Conclusion for Safety Design

For cyclists and safety engineers, the takeaway is that “loudness” is not a single number on a decibel meter. It is a neurological event. By utilizing two tones separated by a specific interval (roughly 15-20% of the frequency), a warning device can hack the human auditory system to appear louder, more urgent, and more “real” than a single tone of equivalent power.16171819

References

Footnotes

-

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. “Regulation No. 28: Audible warning devices.” Consolidated text (2010). EUR-Lex PDF. ↩

-

American Academy of Audiology. “Levels of noise in decibels (dB).” Educational poster listing car horns ≈110 dB and common environmental sounds. PDF. ↩

-

World Health Organization. “Deafness and hearing loss: Safe listening.” Q&A (2025). WHO safe listening. ↩

-

Cedolin, L., & Delgutte, B. “Spatiotemporal representation of the pitch of harmonic complex tones in the auditory nerve.” Journal of Neuroscience 30(4), 12734–12744 (2010). PMC article. ↩

-

Larsen, E., & Delgutte, B. “Pitch representations in the auditory nerve: two concurrent complex tones.” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 123(3), 1637–1655 (2008). MIT DSpace summary. ↩

-

Su, Y., Delgutte, B., & Colburn, H. S. “Pitch of harmonic complex tones: rate-place coding of pitch in the auditory nerve.” bioRxiv 2019. Preprint. ↩

-

Plomp, R., & Levelt, W. J. M. “Tonal consonance and critical bandwidth.” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 38(4), 548–560 (1965). JASA abstract. ↩ ↩2

-

Vassilakis, P. N. “Perceptual and physical properties of amplitude fluctuation and their musical significance.” Music Perception 21(3), 313–336 (2004). (Summarized and extended in later consonance models drawing on Plomp & Levelt.) See overview in Semantic Scholar summary of Plomp–Levelt. ↩

-

“Vehicle horn.” Wikipedia (rev. 2025). Section on horn frequencies and dual-tone designs. Vehicle horn article. ↩

-

Lemaitre, G., Susini, P., Winsberg, S., McAdams, S., & Letinturier, B. “The sound quality of car horns: A psychoacoustical study of timbre.” Acta Acustica united with Acustica 93, 457–468 (2007). PDF. ↩

-

Toyota / Hella. “Electric twin horn, frequency 400 Hz low tone / 500 Hz high tone.” Product listing (accessed 2025). Example product. ↩

-

PIAA Corporation. Marketing material and independent tests describing 400/500 Hz dual-tone sports horns (2019–2024). Example comparison: BMWSportTouring horn tests. ↩

-

Feng, L., & Wang, X. “Harmonic template neurons in primate auditory cortex underlying complex sound processing.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(5), E840–E848 (2017). PNAS article. ↩

-

Fishman, Y. I., Micheyl, C., & Steinschneider, M. “Neural representation of concurrent harmonic sounds in monkey primary auditory cortex.” Journal of Neuroscience 34(37), 12425–12438 (2014). JNeurosci article. ↩

-

Wang, X. “The harmonic organization of auditory cortex.” Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 7, 114 (2013). PMC article. ↩

-

Kang, H. S., Park, S. H., & Lee, K. H. “Quality index of dual shell horns of passenger cars based on a spectrum decay slope.” International Journal of Automotive Technology 16, 237–244 (2015). Springer article. ↩

-

Mollah, A. A., et al. “Intelligent classification of automotive horn sound quality.” Transportation Research Record (2024). TRID record. ↩

-

Kim, S. Y., et al. “Methodology for sound quality analysis of motors using psychoacoustic parameters.” Applied Sciences 12(17), 8549 (2022). PMC article. ↩

-

Wang, Y. S., et al. “A sound quality model for objective synthesis evaluation of vehicle interior noise.” Applied Acoustics 74(10), 1141–1149 (2013). ScienceDirect. ↩